The Minimum Every Developer Must Know About AI Models (No Excuses!)

The baseline knowledge every developer needs to use AI tools without breaking things

In 2003, Joel Spolsky wrote required reading: “The Absolute Minimum Every Software Developer Must Know About Unicode and Character Sets (No Excuses!).” This is my 2025 version.

If you’re a developer in 2025 who doesn’t know the basics of how AI models work, and I catch you, I’m making you debug a hallucinated codebase for six months. I swear.

Developers everywhere use AI coding assistants—ChatGPT, Copilot, Cursor, Kilo Code. The problem is that too many have no idea how these tools actually work. We treat AI like a magical oracle. We act shocked when the same prompt gives different results. We paste entire codebases and wonder why it “forgot” requirements. We deploy blindly trusted code to production.

It’s the developer equivalent of a doctor who doesn’t believe in germs.

This guide is to equip you with exactly what every working developer must know about AI models. No PhD required. No transformer architectures. Just the baseline knowledge to use these tools without causing disasters.

Right now, most developers are way below that baseline.

Don’t paste another line of code into an AI assistant until you finish this article.

How AI Models Work (The High-Level TL;DR)

Your Mental Model: Pattern Matching, Not Code Execution

Forget the magic. A Large Language Model (LLM)—the engine behind AI coding assistants—is fundamentally a sophisticated calculator for text. Its core function is to perform one task, over and over: predict the next token.

When you write a prompt, the process follows a simple, three-step loop:

Tokenization: Your prompt text is first converted into the model’s native language, tokens. A token is the foundational unit of data the model processes—a chunk of text that is roughly three-quarters of a word, but can be an entire word, a punctuation mark, or even a piece of indentation. This initial step determines the cost and the space remaining in your context window.

Statistical Prediction: The model analyzes the entire context—your tokenized prompt, all previous conversation, and any files it has access to. It then calculates, based on the petabytes of data it was trained on, the statistically most probable next token to follow the sequence. It’s a massive, probabilistic pattern-matching exercise. It doesn’t “understand” your code or “reason” about the problem; it suggests the pattern that has been most common in similar codebases.

Generation Loop: The model outputs that single token, adds it to the end of the context, and immediately returns to step 2 to predict the next token, and so on. This repeats thousands of times per second until the model hits a stop condition (like generating a closing bracket or reaching the maximum length).

Why this matters: Everything you see—a function, a 10-line bug fix, a documentation summary—is the result of this token-by-token prediction loop. The entire output is a highly educated guess. This foundation is responsible for a few characteristics of programming with AI:

Prompts are not code: You are giving the model a starting point for a prediction, not an instruction for a deterministic computer.

Results are non-deterministic: A parameter called temperature adds a controlled level of randomness to the statistical choice, which is why the same prompt yields different code every time.

The context window limits everything: The entire conversation history must fit within the token limit for the model to “remember” the full picture.

This mental model of predictive pattern-matching—not logical execution—is the absolute minimum you need to use these tools responsibly. Now let’s dive into what this all means for your code.

Prompts Are Not Code: Expect Non-Deterministic Results

Let’s start with the most important thing: prompts are not code.

When you write if (x > 5) { return true; }, you get the exact same behavior every single time. That’s the entire point of programming. Determinism. Reproducibility. The computer does exactly what you tell it to do. And most developer tools (even Jenkins, I’m told, but I’m not sure) work in deterministic ways.

Prompts don’t work that way. At all. Asking a model to do something is more like asking a junior teammate to do something for you than issuing precise instructions to a computer.

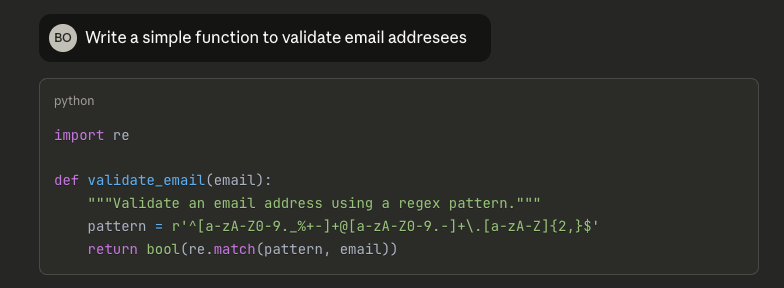

I asked Claude to write a simple function to validate email addresses. Three times. Same exact prompt. Here’s what I got:

Attempt 1:

Attempt 2:

Attempt 3:

All three responses are technically “correct”. None match what I would’ve written. They’re not even in the same language. If I accepted the first without thinking, I’d ship a regex with untested edge cases.

What’s actually happening: AI models generate statistically likely text based on training patterns. They don’t execute prompts like code. Temperature adds randomness. Internal state varies. Your prompt is a suggestion, not an instruction.

The disaster: You refactor a function. It works. You ship it. Three weeks later, your colleague requests the same refactor, but this time the model generates something subtly different. Now you have incompatible implementations, and nobody knows why.

Bottom line: Verify everything. AI output is a first draft from an unreliable collaborator. You wouldn’t ship unreviewed code from a junior developer—don’t ship unreviewed AI code either.

Reasoning vs. Pattern Matching: What AI Doesn’t Get About Your Codebase

AI models don’t “understand” your code. They don’t “think about” your architecture. They don’t “reason through” your problem. They predict tokens.

Given everything before, what token comes next? Repeat until done.

This can produce impressive results. The models have seen massive amounts of code. Their pattern matching is sophisticated. They generate syntactically correct code in dozens of languages, follow complex instructions, even explain their “reasoning.”

But it’s not reasoning. Pattern matching at genius speed isn’t the same as understanding at human depth.

Why this matters: The model doesn’t understand your specific context. It’s seen millions of codebases and suggests patterns that match prior experience.

If your codebase has:

Unusual conventions

A custom framework

Domain-specific constraints

Other quirks

The model might confidently suggest patterns that look right but don’t fit.

Example: A model suggested moment.js for date handling in a codebase standardized on date-fns three years ago. Perfectly fine code—for a different codebase. In context, a maintenance nightmare.

The disaster: You ask for a feature implementation. The model generates code following a common pattern from training data—maybe even a pattern you once used. But you refactored away from it six months ago for good reasons. The model doesn’t know. It just knows what looks likely.

The fix: Be explicit about constraints. Don’t assume the model knows your conventions. Tell it: “We use date-fns, not moment. We follow this error handling pattern. Our coding standard requires...”

Knowledge Cutoff and Limitations: What AI Doesn’t Know About Anything

One more limitation about LLMs to be aware of: AI models are trained on data up to a certain date. They don’t know anything about what happened after.

Models don’t know things like details of libraries released after training cutoff, recent security vulnerabilities, API changes and deprecations, etc.

The disaster: You ask how to implement authentication for a new library. It suggests an approach that was standard during training but has since been deprecated due to a security vulnerability. You implement it. You ship it. Six months later, you get breached.

The model isn’t lying. It’s telling you what it knows, or making its best guess when what it knows is outdated.

The fix: Verify security-related or newer library code against current documentation. Better yet, use tools like Context7 that ensure agents have access to latest docs. Models excel at explaining concepts and generating boilerplate—they’re not replacements for reading actual docs.

Tokens ≠ Characters: The Real Size and Cost of Inputs and Outputs

Developers hit context limits without understanding why. They paste 50,000 characters (”not that much!”) and wonder why the model chokes. The disconnect is that they think in characters, while models think in tokens.

Tokens ≠ characters ≠ words. Tokens are text chunks that the model processes as single units—roughly three-quarters of a word on average. But “average” hides crucial variation.

Examples:

“indentation” = 2-3 tokens

getUserAccountBalanceByIdAsync = 6+ tokens (splits at word boundaries)

Whitespace and special characters = often their own tokens

Different languages tokenize differently

Try this: The same logic in Python vs. minified JavaScript. Python uses dramatically more tokens (readable names, comments, whitespace). Minified JS is denser—same functionality, fewer tokens.

This matters because every model has a context window measured in tokens, not characters:

Claude Sonnet 3.7: ~200K tokens

GPT-5.1: ~400K tokens

Claude Sonnet 4.5: ~1M tokens

Various models: anywhere from 4K to 1M+

When you hit the context limit, you’re hitting a token budget—not a file size limit. That budget includes your input AND the model’s response (this matters for pricing too).

The disaster: A long debugging session. You’ve pasted code for an hour. Suddenly the model gives nonsense or truncates responses, because you’ve silently exceeded the context window. The model works with incomplete information but won’t tell you—it just confidently delivers wrong answers.

The bottom line: Managing context is critical for model success.

Context Windows Limit Everything: The “Lost in the Middle” Problem

“GPT-5.1 has a 400K token context window! That’s huge!”

Sure. My car tops out at 140 mph, but that doesn’t mean I should drive that fast. Even huge context windows have their limitations.

The stated context window is a maximum, not a recommendation. Performance degrades significantly as you approach limits. Research shows the “lost in the middle” problem: models pay the most attention to the beginning and end of your conversation, losing track of middle information.

Think of a long meeting. You might remember opening agenda items and closing action items clearly, but that middle discussion about database schema? Fuzzy.

Developers have 30-message conversations with Claude, explaining architecture in message 3, coding standards in message 7, constraints in message 12. Then wonder why message 28 violates all three.

What’s happening: Middle messages have less influence than you’d expect. Recency bias favors recent context, while position bias favors the beginning and end.

How to avoid the context trap: Re-state critical requirements in your most recent message. Don’t assume the model retains earlier information—brief it like a new team member every time.

Tokens and Pricing and Rate Limits (Oh My!)

Token counts and context window limitations don’t only have an impact on performance; they also significantly influence costs. If developers aren’t judicious with token use (in both input and output), they can find themselves locked out, or land you with a surprise bill.

Pricing Models Aren’t Intuitive

AI pricing seems simple: pay-per-token. Input costs X, output costs Y.

Except that output tokens cost 3-5x more than input. Nobody thinks about this when prompting.

Two ways to ask for a code refactor:

Expensive: “Show me the complete refactored file with all changes applied.”

Cheap: “Show me just the changes needed, in diff format.”

The first prompt generates 500 lines of code for 10 changed lines. That’s 500 lines of output tokens. The second prompt generates 30 lines. You just saved 90%.

Multiply that by a hundred requests daily across your team.

Claude Sonnet 4 pricing:

Input: $3 per million tokens

Output: $15 per million tokens

That 5x difference means that every verbose response costs five times more per token than your prompt.

The disaster: The team adopts AI enthusiastically. Everyone requests “complete implementations” and “full file rewrites.” Nobody considers cost optimization. Your monthly bill jumps from $500 to $15,000, finance freaks out, and now AI is banned company-wide.

The fix: Think about the output length when prompting. Request diffs, not full files. Ask for explanations only when needed, and set up cost monitoring before you need it.

Rate Limits Are Real

It’s 4:47 PM on a Friday. You’ve been debugging a production issue for three hours. You finally figure out the problem and need to generate a fix. Not only that, but you prompt your AI assistant and get:

Error 429: Rate limit exceeded. Please try again in 47 minutes.

Rate limits exist because inference is expensive. Every model provider has them, measured in:

RPM: Requests per minute

TPM: Tokens per minute

RPD: Requests per day

These limits are shared across your entire API key, organization, or account tier.

That means there are dozens of ways you can get burned:

Your teammate batch-processes 10,000 code documentation requests during your production incident? You’re both locked out.

Your CI/CD pipeline uses AI for code review, but the same API key handles developer ad-hoc queries. Now your deployment is blocked.

Someone pushes 50 PRs for a migration. The pipeline burns through your rate limit and nobody can use AI until reset.

Pay-as-you-go avoids this

The pay-as-you-go approach to API access can help avoid rate limit issues because it allows for centralized team management and proactive monitoring of usage with analytics. This setup often allows developers to automatically use multiple model providers as a failover, so a surge in usage on one key or service doesn’t block the entire team’s ability to use AI (unlike a system tied to a single, shared rate-limited tier).

Reality Check: Security and Privacy

Pop quiz: When you use Claude in your company’s internal tool, where does your code go?

If you answered “Anthropic,” you might be wrong.

Inference Providers vs. Model Creators

The AI landscape has a crucial distinction that most developers don’t understand: model creators (Anthropic, OpenAI, Google, etc.) are often different from inference providers (AWS Bedrock, Google Cloud Vertex AI, Azure OpenAI, various startups).

A model creator is the company (like Anthropic or OpenAI) that trains, develops, and publishes the core AI model (the LLM). An inference provider is the entity (like AWS Bedrock or Azure OpenAI) that hosts, runs, and manages the infrastructure for you to actually send a prompt and receive a response (the inference step).

When you “use Claude,” you might be:

Using claude.ai directly (Anthropic’s infrastructure)

Using the Anthropic API (Anthropic’s infrastructure)

Using AWS Bedrock (Amazon’s infrastructure)

Using Google Cloud’s Vertex AI (Google’s infrastructure)

Using some third-party tool that calls one of the above

Each has different data handling policies, compliance certifications, geographic locations, and privacy guarantees.

Your company’s security policy says “no sending code to external AI providers.” Does it specify which providers? Is your tool compliant? Does your dev team know?

Most breaches happen because of this gap. Security approves “Claude.” Developer installs an extension that routes through a third-party provider with different policies. The provider gets breached; your code leaks.

Do this before your next AI prompt:

Open your AI tool’s settings

Find the “About” or “Privacy” section

Identify the actual inference provider

Read their data retention policy

Verify it matches your security requirements

Your Code Is Training Data (The Default is Not Private)

Here’s a fun interaction:

You: pastes company’s authentication logic into ChatGPT web interface

OpenAI’s Terms: “We may use your content to improve our models...”

You: “Wait, what?”

Web interfaces for AI tools have different data retention policies than APIs. By default, web conversations may be used for training. API calls typically aren’t, but verify this.

Why this matters: Everything you paste could influence future model outputs. Patterns from your authentication logic could appear in code suggestions for other users. Free AI tools are like other free SaaS items in the past: you’re not the customer, your code is the product.

Model providers now offer zero-retention options, enterprise tiers with stronger guarantees, and clear opt-outs. But you must actually use them.

What you should do:

Know your tool’s data retention policy

Use API access with zero-retention for sensitive code

Choose tools that never train on your data

When in doubt, don’t paste it

The Bottom Line

Yes, this is a lot. You came to write code faster. I just gave you nine (new) things to worry about.

But here’s the reality: These tools are genuinely incredible. The most significant productivity enhancement since Stack Overflow. Maybe since the IDE. Maybe since the compiler.

You can’t use them effectively without understanding what they actually are.

AI coding assistants ARE:

Incredibly fast pattern matchers

Great at boilerplate and common patterns

Useful for explaining and documenting code

Productivity multipliers when used correctly

Liabilities when used naively

AI coding assistants are NOT:

Deterministic tools (same input ≠ same output)

Current knowledge bases

Reasoning engines that understand your architecture

Secure by default

Free (even when they seem free)

Now you know the minimum.

Stop treating AI like magic: blindly trusting output, or ignoring context limits, costs, and privacy.

Go back to programming—using AI as the powerful but nondeterministic tool it actually is.

Choose tools built with these realities in mind. And if I catch you deploying hallucinated code to production? You’ll explain what a token is to every PM in your company. Twice.

Fantastic Article 👍

Essential read! Understanding that AI coding assistants are pattern matchers, not reasoning engines, is the baseline for using them safely and effectively in production.

I talk about the latest AI trends and insights. If you’re interested in using AI coding assistants effectively while avoiding costly mistakes and understanding their limits, check out my Substack. I’m sure you’ll find it very relevant and relatable